UNI speaker focuses on race

“I think we are on our way to a better place, but I think we have to roll up our sleeves and work to get there. When I say “we,” I am talking about the great, big, royal, capital “we.” It’s everybody’s work. Race is no longer a spectator sport for anybody. It impacts all of us. I don’t care if you came here on a luxury liner or a slave ship, or if you crossed a border, or if you entered on a Learjet. It doesn’t matter. We’re all on the same boat now. We need to figure out how to coexist with each other and remain tethered to each other, even if we don’t agree,” Michele Norris, the founder of the Race Card Project and former co-host of National Public Radio, said.

“I think we are on our way to a better place, but I think we have to roll up our sleeves and work to get there. When I say “we,” I am talking about the great, big, royal, capital “we.” It’s everybody’s work. Race is no longer a spectator sport for anybody. It impacts all of us. I don’t care if you came here on a luxury liner or a slave ship, or if you crossed a border, or if you entered on a Learjet. It doesn’t matter. We’re all on the same boat now. We need to figure out how to coexist with each other and remain tethered to each other, even if we don’t agree,” Michele Norris, the founder of the Race Card Project and former co-host of National Public Radio, said.

Norris came to UNI and the Gallagher Bluedorn on January 30 to speak about “The Grace of Silence,” her memoir about the hidden stories of race within her family.

Norris stumbled upon these stories accidently. She was planning to write a book about the average American’s view of race after Obama was elected; however, Norris was out to breakfast one morning with her grandfather when he became fussy that people weren’t as grateful, and he blurted out, “You know your father was shot.”

Norris did not know this because her late father told almost no one in his family about this, including his then wife, so Norris did some digging. She found out that he was shot in the leg by a white policeman in 1946 while he was entering a building to vote.

But she didn’t stop there. She also found out her grandmother was an Aunt Jemima representative. Her grandmother traveled around a six-state region, including Iowa and Minnesota, something that women, especially African American women did not do at the time. Her grandmother would go from town to town trying to convince people to switch from homemade pancakes to convenience cooking through demonstrations of how to use the simple Aunt Jemima complete pancake mix.

Her parents kept these stories a secret from Norris and her siblings because they loved their country and wanted their children to be as successful as possible while also loving their country.

However, these stories brought race to the forefront of Norris’ mind. They helped Norris realize that race was a conversation the world needed to have.

Realizing that her own family had hidden stories, Norris saw that people didn’t want to have conversations about race or were fearful about having those conversations, so she knew she had to start it.

“I was afraid that I would face people who would cross their arms and cross their legs and rather bite their toenails than engage in a conversation about race, so I thought I have to figure out how to lubricate this conversation somehow, and the thing that I came up with was the Race Card Project,” Norris said.

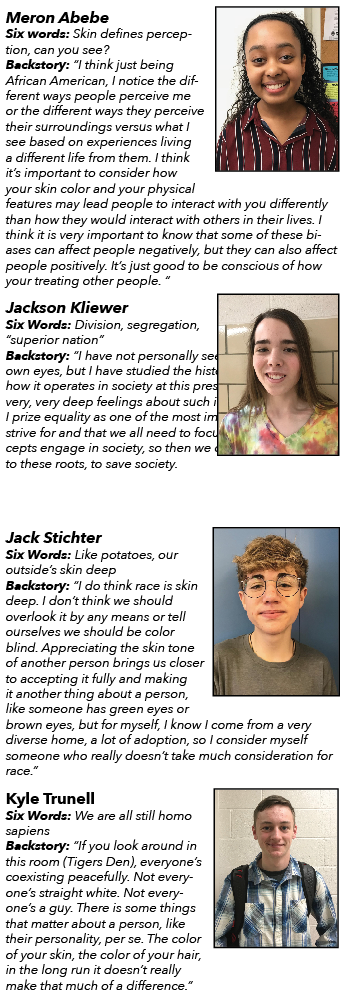

Norris did some brainstorming and landed upon different exercises. She started with a one word exercise and worked her way up to six. She knew that people are often described by one word, a word that may be a genuine description, or a stereotype, so she gave people six words.

“Sometimes that word feels good, and maybe you could own it, but sometimes it doesn’t feel so good because you’re so much more than that,” Norris said. “No one word could possibly describe us. So, we decided to give people six words. Think about the word race. Then whatever comes into your mind, your memories, your laments, your triumphs, your anthems, your perspective, your viewpoints. Whatever you want to say, but you only get six words.”

Norris had formulated this idea, but she wanted to see if it would catch on. Thus, Norris created postcards that consisted of the six word exercise and the outlet where people could express their six word story.

“I was on a 35 city book,” she said. “I would leave these postcards wherever, and I wondered if people would take the bait. Pretty quickly it became clear that people wanted to share their stories.”

Soon life stories that were reflected in six words started flooding Norris’ Inbox.

“‘White not allowed to be proud,’

“I’m only Asian when it’s convenient,’

“Lady, I don’t want your purse,’

“Black children cost less to adopt,’

“No, you cannot touch my hair,’

“So, I knew I had to keep going,” Norris said.

When the cards started to come in, they would send in their six words, and Norris also asked them to send in their back story and a picture.

“Now more than eight years later,” Norris said. “We have 250,000 stories archived. They come from every state in our country. They come from more than 70 other countries and together create this wonderful archive. They help me understand perspectives that I could not get to when I was in Studio 2A in NPR. It becomes this tap root that helps me understand America in a different way.”

Norris left her job at NPR for the Race Card Project and jumped in with no regrets. “I left my job at Public Radio, so I could dedicate my time to this crazy project. I spent so many years in public radio asking people to listen to me. Now I am asking them to listen to each other,” Norris said.

She now reaps the benefits of taking this project head on. “I now stand before you as someone for whom race is at the center of my portfolio,” Norris said. “Because of this, my world did not get smaller. It got so much bigger. I was able to understand America in a particular way because I put my ear to a conversation that we often run away from.”

To submit your six words, visit theracecardproject.com

You must be logged in to post a comment Login