An Iowa Watch Investigation | Midwestern fish eating guidelines vary

Maria Christensen, of Waterloo, fishes at Big Woods Lake in Cedar Falls, Iowa, on May 21.

On a chilly morning in April, Gunwoo Yoon, his wife and two sons joined about 100 other anglers at Prairie Lakes in Cedar Falls. They were fishing for trout, and plenty were available as the Iowa Department of National Resources (DNR) was doing its annual stocking of the lake. Hundreds of trout gushed from a tank truck through a pipe into the lake.

“We moved last year to Cedar Falls, and it was the first time that we went fishing at the trout stocking event,” Yoon, a University of Northern Iowa assistant professor of marketing, said. “It was a super family-oriented fishing event, so we were there. I would say that we go fishing about one time per month since then.”

The rainbow trout released into Prairie Lakes were fine to eat because they came from a hatchery, but trying to distinguish what fish to eat from one Midwest state to the next can be difficult because the rules vary in each state, an IowaWatch/Cedar Falls Tiger Hi-Line investigation showed.

Even with fish sampling, it is hard to know where to fish because fish from only a few waterways where people fish are tested each year, the investigation showed. Anglers at farm ponds are on their own in regard to the health of the fish they catch because the DNR does not sample fish in private water bodies for contamination.

The state warns Iowa anglers to limit their consumption of wild caught fish in 22 lakes and river sections around the state due to contaminants like mercury and PCBs, but 78% of Iowans did not limit their consumptions based on recent concern, according to an unpublished 2018 Iowa Angler Survey.

Mercury and PCBs are industrial byproducts and tend to concentrate into the fatty tissues of many fish.

The Iowa DNR lists advisories on its website, but interviews from sporting goods stores revealed that people often are not told to look at the guidelines online or pick up a guideline pamphlet when they buy their fishing license. “We do have little booklets, straight from the DNR that are free that have anything that you want to know about fishing, but we don’t hand them out,” Coleman Waters, a customer service employee from the Cedar Falls SCHEELS, said.

Yoon got his fishing license from a sporting goods store. “But no one told me or informed me about these chemicals in the fish,” he said.

A man fishes on Big Woods Lake in Cedar Falls, Iowa, on May 21.

A 2007 survey by the Responsive Management National Office of Licensed Anglers in Iowa showed that 81.6 percent of anglers consume at least some of the fish they harvest and approximately 4.6 million meals of Iowa-caught fish were consumed. Of those anglers that harvested fish, 78 percent said they did not limit their consumption for safety concerns and 88 percent considered fish caught from Iowa to be safe to eat.

“I don’t know how that goes, for the chemicals and stuff,” Maria Christensen, a fisher from Waterloo, Iowa, said. Although she said she worries about the health of eating fish, she thinks the waters are safe. “But if it was contaminated, I know they wouldn’t allow you to go there.”

DIFFERENT

STANDARDS

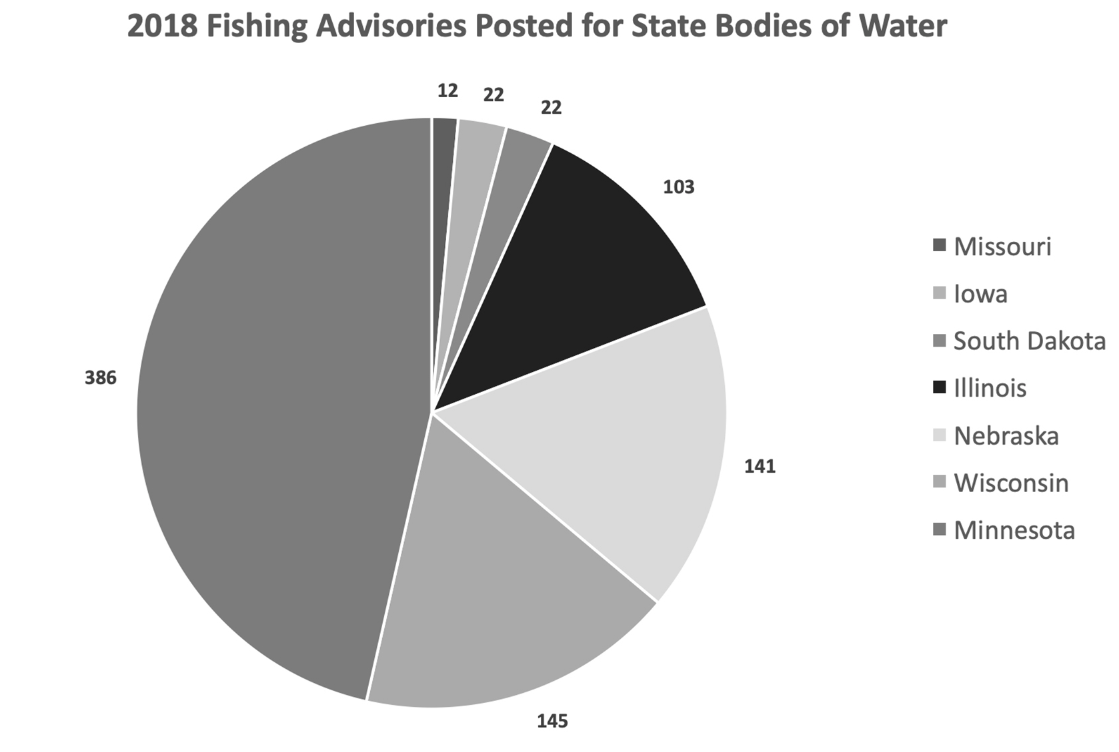

Science in the Media Graphics

The standards for what makes a fish healthy for eating can change over time. In 2018, the Minnesota Department of Health changed its risk assessment for perfluorooctane sulfonate chemicals (PFOS). Based on updated science, the department announced it had changed the level at which it advises people to restrain from eating fish from 800 ng/g (nanograms per gram) to 200 ng/g. The new standards meant that anglers were advised not to eat any fish from Lake Elmo, just east of the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area.

But learning what makes a fish healthy enough to eat also depends on who’s giving the information, and where. For example, Iowa defines fish portion sizes as 6 ounces for an adult. In Nebraska, advisories are based on “an 8-ounce meal because we believe that it is realistically more of what a person would sit down and consume for a meal,” Greg Michl, Nebraska’s fish tissue program coordinator, said.

Also, Midwest states vary on who much testing they do.

•Iowa tests 20 locations from its rivers and lakes, with a different group of sampling locations each year.

•South Dakota tested 14 water bodies in 2018.

•Nebraska tests approximately 40-50 pre-selected streams and publicly owned lakes in two or three of Nebraska’s 13 major river basins annually.

•Illinois tests 40-50 streams, rivers and inland lakes and four Lake Michigan open water stations each year.

•Wisconsin collects fish from approximately 50 to 100 sites each year.

•Minnesota tests fish samples from approximately 130 lakes and river segments each year.

The Iowa DNR recommends that people eat no more than one meal per week of any predator fish caught in the Iowa River stretch between the upper end of Coralville Lake near Swisher, in Johnson County, to the Coralville Dam southeast of North Liberty, because of potential mercury contamination.

Likewise, the DNR recommends no more than one meal per week limit on any channel catfish caught in McKinley Lake in Union County because of the PCB contamination.

Nebraska recommends that fish consumption be limited to one 8-ounce serving per week because of mercury levels present in fish.

In Wisconsin, state officials recommend that women of childbearing age, or under 50, and children under 15 eat one serving per week of bluegills, crappies and yellow perch; one serving per month of walleye, pike and bass; and no muskies. The state does not restrict the consumption of bluegills, crappies or yellow perch for women over 50 or men, and it recommends one serving per week of walleye, pike and bass; and one serving per month of muskies.

Minnesota says smaller fish like crappies, yellow perch, bullheads and sunfish do not need to be limited, but larger fish like walleyes, northern pike and lake trout should only be eaten once a week, the state recommends. Commercial fish like shark and swordfish should only be eaten once a month, it recommends.

Patricia McCann, a research scientist with the Minnesota Department of Health, said Minnesota bases its guidelines on a risk-based approach and communicates it to the public. “We want people to follow our guidelines, and if they follow our guidelines, then I’m not concerned about their exposure,” she said.

Barry Eastman, an angler from Cedar Falls, said he is not worried about the chemicals in the fish because he does not consume fish regularly. “Since we only eat fish only half a dozen times a year, I’m not too worried about it. If I was going out and catching fish in the river every day, that’s not good ’cause I know the water is polluted. It’s full of nitrates and bad stuff,” he said.

“If I would eat more of it, I would say that was definitely something I would be concerned with,” Cedar Falls fisherman Aaron Wilson said. Wilson said he fishes mostly for pleasure but eats about 10 fish a year, usually walleye.

Although the Iowa DNR, along with other states, publishes guidelines, they are only recommendations. “Fish consumption advisories are not legal requirements, and there is no penalty if an individual chooses not to follow these recommendations. The Iowa DNR does not set regulations or restrictions related to contaminants in fish flesh,” the DNR’s Krier wrote.

The fish consumption guidelines provided by Iowa, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, Nebraska, South Dakota and Missouri address the size and frequency of fish an average person should consume taking account factors such as age and gender.

The most sensitive populations for fish contaminants are pregnant women and children. Iowa’s fish consumption guidelines provided by the DNR suggest that people who are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, nursing or under age 12 limit consumption of predator fish like walleye and bass to one meal per week

Nevertheless, DNR officials in the various Midwest states still want to promote fishing and the consumption of fish.

“An important factor to this whole situation is fish are very good for people to eat, not losing sight of that, but just paying attention to where your sources of fish come from and obviously local fish caught from various states,” Michl said.

MAINTAINING

BUSINESS

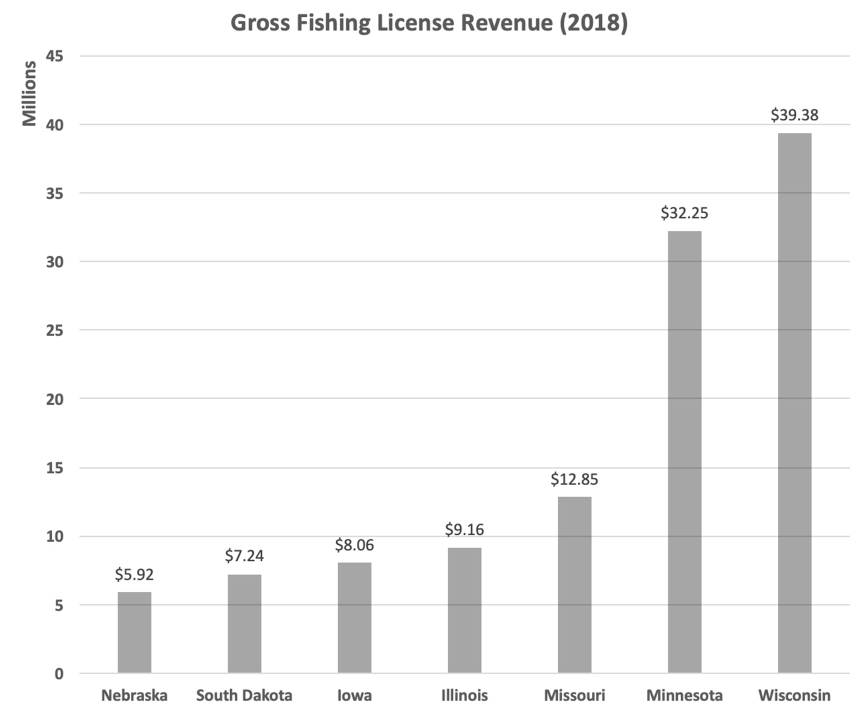

Science in the Media Graphics

Fishing in Iowa is a big business and heavily promoted by the Iowa DNR, with lists of fishing locations and hot spots on its website. In 2018, Iowa earned more than $8 million in revenue on fishing licenses.

Fishing guidelines are available at the various spots where people may purchase fishing licenses, including sports and outdoors stores, and grocery stores. The DNR also posts fishing guidelines on its website.

Fishing is also a big business and recreational activity in the Midwestern states adjacent to Iowa: Missouri, South Dakota, Nebraska, Illinois, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Wisconsin has the largest fishing economy of these states, earning more than $39 million annually in fishing licenses. Each state also issues fish consumption advisories. Contaminants include mercury, lead, PCBs, chlordane, dioxin, perfluorochemicals (PFCs) and perfluorooctane (PFOS).

For anglers in the Midwest, trying to distinguish which fish are safe to eat is a dizzying task because of each state’s different guidelines. According to a 2018 report by Michl, the disparities between states lead to a confusing system.

“While nearly every state in the U.S. has a fish tissue monitoring program in place, differences exist in the way fish samples are analyzed and assessed between states,” the report said. “These differences create a lack of comparability between states and can cause confusion for people who enjoy fishing in their home state, shared waters and other states’ waters.”

Even with annual fish tissue sampling, it is impossible in some Midwestern states to know the fish quality in every location. Minnesota has sampled about 1,200 lakes, or only 22 percent of the state’s 5,500 fishing lakes, since it started testing fish for contaminants since 1967. Similarly, Wisconsin, with 15,000 lakes and 32,000 miles of rivers, only has tested fish from about 1,700 sites since the 1970s.

The Iowa DNR has collected annual samples of fish tissue since 1980 to determine if contaminants like chlordane, methylmercury and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are below safe levels for human consumption.

Mercury is the most common fish contaminant across the country, largely due to pollution from coal burning power plants that settles into water bodies. Mercury tends to concentrate in the fatty tissue of fish. Larger predator fish tend to have higher concentrations of mercury because they eat smaller fish.

According to the World Health Organization, mercury may pose a threat to child’s development in utero and health early on in life. Mercury can have toxic effects on nervous, digestive and immune systems and on skin, lungs, kidneys and eyes.

In Iowa, the goal is to regularly take fish samples for testing from popular public fishing sites every 10 years and from key river segments every five years, Ken Krier, of the Iowa DNR water monitoring staff, wrote in an email.

“However, because there are about 130 SPOLs (Significant Publicly-Owned Lakes) and hundreds/thousands of miles of fishable rivers, that didn’t happen due to the very large demands on funding and staff time,” he wrote in the email. Krier said that of the 301 sites sampled since 1980, 126 sites have been sampled once, 50 sites have been samples twice, 40 sites have been sampled three times, 26 sites sampled four times, 19 sites sampled five times and 40 sites sampled more than five times.

In addition, the DNR maintains some sites to find trends, charting their long-term health of fish stock in certain bodies of water. Since 2016, it has followed 15 sites, sampling the fish every other year.

FISH CONSUMPTION

RECOMMENDATIONS

Fishing reports from Midwest states provide citizens with health guidelines for consuming fish but also the benefits.

Missouri’s fish advisory summary has a full page of health benefits, stating that fish are a part of a healthy diet. The summary states that consuming fish improves learning ability in children, decreases triglycerides, lowers blood pressure, reduces blood clotting and enhances immune function.

Nebraska’s fishing brochure is called “Eat Safe Fish in Nebraska.”

Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois offer their fishing advisories in multiple languages but not Iowa and its other neighbors, despite the wide span of ethnicities in the United States.

Minnesota Department of Health translates its statewide fishing guidance into Hmong, Spanish and Vietnamese and has provisions for Braille communication.

In addition to providing their fishing advisory in English, Spanish and Laotian, Wisconsin offers an alternative advisory phone number for Braille communication as well as an audiotape and large print. “We continuously try to learn more about how people are receiving our messages and better ways to do it. We are always trying to improve,” McCann said.

Besides fishing advisories posted online and in stores, Minnesota shares information with the state about fish consumption safety in alternative ways. “We work with health care providers. We have things on our website, YouTube videos. We have tasty videos about recipes,” McCann, the state Department of Health research scientist, said.

“We have done focus groups with woman to see how they want to receive information and what are the barriers in eating fish. We do surveys, and we work with communities that we think eat more fish, like the Hmong community in Minnesota,” she said.

Unlike the other Midwest states, the Missouri DNR engages a younger audience to understand fishing advisories early in their life. The state provides the public with a fish advisory activity book to engage young ones. This book contains information in an entertaining way about different topics like the biomagnification of mercury in fish, lead poisoning and the different types of fish.

Cedar Falls fisherman Troy Slater said he is conscious of the health effects of eating fish contaminated with chemicals. “I’ve talked to kids who have grown up in Cedar Falls who have fished the Cedar but won’t eat anything out of it just because of all of the runoff. I think about it,” he said.

On a chilly morning in April, Gunwoo Yoon, his wife and two sons joined about 100 other anglers at Prairie Lakes in Cedar Falls. They were fishing for trout, and plenty were available as the Iowa Department of National Resources (DNR) was doing its annual stocking of the lake. Hundreds of trout gushed from a tank truck through a pipe into the lake.

“We moved last year to Cedar Falls, and it was the first time that we went fishing at the trout stocking event,” Yoon, a University of Northern Iowa assistant professor of marketing, said. “It was a super family-oriented fishing event, so we were there. I would say that we go fishing about one time per month since then.”

The rainbow trout released into Prairie Lakes were fine to eat because they came from a hatchery, but trying to distinguish what fish to eat from one Midwest state to the next can be difficult because the rules vary in each state, an IowaWatch/Cedar Falls Tiger Hi-Line investigation showed.

Even with fish sampling, it is hard to know where to fish because fish from only a few waterways where people fish are tested each year, the investigation showed. Anglers at farm ponds are on their own in regard to the health of the fish they catch because the DNR does not sample fish in private water bodies for contamination.

The state warns Iowa anglers to limit their consumption of wild caught fish in 22 lakes and river sections around the state due to contaminants like mercury and PCBs, but 78% of Iowans did not limit their consumptions based on recent concern, according to an unpublished 2018 Iowa Angler Survey.

Mercury and PCBs are industrial byproducts and tend to concentrate into the fatty tissues of many fish.

The Iowa DNR lists advisories on its website, but interviews from sporting goods stores revealed that people often are not told to look at the guidelines online or pick up a guideline pamphlet when they buy their fishing license. “We do have little booklets, straight from the DNR that are free that have anything that you want to know about fishing, but we don’t hand them out,” Coleman Waters, a customer service employee from the Cedar Falls SCHEELS, said.

Yoon got his fishing license from a sporting goods store. “But no one told me or informed me about these chemicals in the fish,” he said.

A 2007 survey by the Responsive Management National Office of Licensed Anglers in Iowa showed that 81.6 percent of anglers consume at least some of the fish they harvest and approximately 4.6 million meals of Iowa-caught fish were consumed. Of those anglers that harvested fish, 78 percent said they did not limit their consumption for safety concerns and 88 percent considered fish caught from Iowa to be safe to eat.

“I don’t know how that goes, for the chemicals and stuff,” Maria Christensen, a fisher from Waterloo, Iowa, said. Although she said she worries about the health of eating fish, she thinks the waters are safe. “But if it was contaminated, I know they wouldn’t allow you to go there.”

DIFFERENT

STANDARDS

The standards for what makes a fish healthy for eating can change over time. In 2018, the Minnesota Department of Health changed its risk assessment for perfluorooctane sulfonate chemicals (PFOS). Based on updated science, the department announced it had changed the level at which it advises people to restrain from eating fish from 800 ng/g (nanograms per gram) to 200 ng/g. The new standards meant that anglers were advised not to eat any fish from Lake Elmo, just east of the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area.

But learning what makes a fish healthy enough to eat also depends on who’s giving the information, and where. For example, Iowa defines fish portion sizes as 6 ounces for an adult. In Nebraska, advisories are based on “an 8-ounce meal because we believe that it is realistically more of what a person would sit down and consume for a meal,” Greg Michl, Nebraska’s fish tissue program coordinator, said.

Also, Midwest states vary on who much testing they do.

•Iowa tests 20 locations from its rivers and lakes, with a different group of sampling locations each year.

•South Dakota tested 14 water bodies in 2018.

•Nebraska tests approximately 40-50 pre-selected streams and publicly owned lakes in two or three of Nebraska’s 13 major river basins annually.

•Illinois tests 40-50 streams, rivers and inland lakes and four Lake Michigan open water stations each year.

•Wisconsin collects fish from approximately 50 to 100 sites each year.

•Minnesota tests fish samples from approximately 130 lakes and river segments each year.

The Iowa DNR recommends that people eat no more than one meal per week of any predator fish caught in the Iowa River stretch between the upper end of Coralville Lake near Swisher, in Johnson County, to the Coralville Dam southeast of North Liberty, because of potential mercury contamination.

Likewise, the DNR recommends no more than one meal per week limit on any channel catfish caught in McKinley Lake in Union County because of the PCB contamination.

Nebraska recommends that fish consumption be limited to one 8-ounce serving per week because of mercury levels present in fish.

In Wisconsin, state officials recommend that women of childbearing age, or under 50, and children under 15 eat one serving per week of bluegills, crappies and yellow perch; one serving per month of walleye, pike and bass; and no muskies. The state does not restrict the consumption of bluegills, crappies or yellow perch for women over 50 or men, and it recommends one serving per week of walleye, pike and bass; and one serving per month of muskies.

Minnesota says smaller fish like crappies, yellow perch, bullheads and sunfish do not need to be limited, but larger fish like walleyes, northern pike and lake trout should only be eaten once a week, the state recommends. Commercial fish like shark and swordfish should only be eaten once a month, it recommends.

Patricia McCann, a research scientist with the Minnesota Department of Health, said Minnesota bases its guidelines on a risk-based approach and communicates it to the public. “We want people to follow our guidelines, and if they follow our guidelines, then I’m not concerned about their exposure,” she said.

Barry Eastman, an angler from Cedar Falls, said he is not worried about the chemicals in the fish because he does not consume fish regularly. “Since we only eat fish only half a dozen times a year, I’m not too worried about it. If I was going out and catching fish in the river every day, that’s not good ’cause I know the water is polluted. It’s full of nitrates and bad stuff,” he said.

“If I would eat more of it, I would say that was definitely something I would be concerned with,” Cedar Falls fisherman Aaron Wilson said. Wilson said he fishes mostly for pleasure but eats about 10 fish a year, usually walleye.

Although the Iowa DNR, along with other states, publishes guidelines, they are only recommendations. “Fish consumption advisories are not legal requirements, and there is no penalty if an individual chooses not to follow these recommendations. The Iowa DNR does not set regulations or restrictions related to contaminants in fish flesh,” the DNR’s Krier wrote.

The fish consumption guidelines provided by Iowa, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, Nebraska, South Dakota and Missouri address the size and frequency of fish an average person should consume taking account factors such as age and gender.

The most sensitive populations for fish contaminants are pregnant women and children. Iowa’s fish consumption guidelines provided by the DNR suggest that people who are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, nursing or under age 12 limit consumption of predator fish like walleye and bass to one meal per week

Nevertheless, DNR officials in the various Midwest states still want to promote fishing and the consumption of fish.

“An important factor to this whole situation is fish are very good for people to eat, not losing sight of that, but just paying attention to where your sources of fish come from and obviously local fish caught from various states,” Michl said.

MAINTAINING

BUSINESS

Fishing in Iowa is a big business and heavily promoted by the Iowa DNR, with lists of fishing locations and hot spots on its website. In 2018, Iowa earned more than $8 million in revenue on fishing licenses.

Fishing guidelines are available at the various spots where people may purchase fishing licenses, including sports and outdoors stores, and grocery stores. The DNR also posts fishing guidelines on its website.

Fishing is also a big business and recreational activity in the Midwestern states adjacent to Iowa: Missouri, South Dakota, Nebraska, Illinois, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Wisconsin has the largest fishing economy of these states, earning more than $39 million annually in fishing licenses. Each state also issues fish consumption advisories. Contaminants include mercury, lead, PCBs, chlordane, dioxin, perfluorochemicals (PFCs) and perfluorooctane (PFOS).

For anglers in the Midwest, trying to distinguish which fish are safe to eat is a dizzying task because of each state’s different guidelines. According to a 2018 report by Michl, the disparities between states lead to a confusing system.

“While nearly every state in the U.S. has a fish tissue monitoring program in place, differences exist in the way fish samples are analyzed and assessed between states,” the report said. “These differences create a lack of comparability between states and can cause confusion for people who enjoy fishing in their home state, shared waters and other states’ waters.”

Even with annual fish tissue sampling, it is impossible in some Midwestern states to know the fish quality in every location. Minnesota has sampled about 1,200 lakes, or only 22 percent of the state’s 5,500 fishing lakes, since it started testing fish for contaminants since 1967. Similarly, Wisconsin, with 15,000 lakes and 32,000 miles of rivers, only has tested fish from about 1,700 sites since the 1970s.

The Iowa DNR has collected annual samples of fish tissue since 1980 to determine if contaminants like chlordane, methylmercury and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are below safe levels for human consumption.

Mercury is the most common fish contaminant across the country, largely due to pollution from coal burning power plants that settles into water bodies. Mercury tends to concentrate in the fatty tissue of fish. Larger predator fish tend to have higher concentrations of mercury because they eat smaller fish.

According to the World Health Organization, mercury may pose a threat to child’s development in utero and health early on in life. Mercury can have toxic effects on nervous, digestive and immune systems and on skin, lungs, kidneys and eyes.

In Iowa, the goal is to regularly take fish samples for testing from popular public fishing sites every 10 years and from key river segments every five years, Ken Krier, of the Iowa DNR water monitoring staff, wrote in an email.

“However, because there are about 130 SPOLs (Significant Publicly-Owned Lakes) and hundreds/thousands of miles of fishable rivers, that didn’t happen due to the very large demands on funding and staff time,” he wrote in the email. Krier said that of the 301 sites sampled since 1980, 126 sites have been sampled once, 50 sites have been samples twice, 40 sites have been sampled three times, 26 sites sampled four times, 19 sites sampled five times and 40 sites sampled more than five times.

In addition, the DNR maintains some sites to find trends, charting their long-term health of fish stock in certain bodies of water. Since 2016, it has followed 15 sites, sampling the fish every other year.

FISH CONSUMPTION

RECOMMENDATIONS

Fishing reports from Midwest states provide citizens with health guidelines for consuming fish but also the benefits.

Missouri’s fish advisory summary has a full page of health benefits, stating that fish are a part of a healthy diet. The summary states that consuming fish improves learning ability in children, decreases triglycerides, lowers blood pressure, reduces blood clotting and enhances immune function.

Nebraska’s fishing brochure is called “Eat Safe Fish in Nebraska.”

Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois offer their fishing advisories in multiple languages but not Iowa and its other neighbors, despite the wide span of ethnicities in the United States.

Minnesota Department of Health translates its statewide fishing guidance into Hmong, Spanish and Vietnamese and has provisions for Braille communication.

In addition to providing their fishing advisory in English, Spanish and Laotian, Wisconsin offers an alternative advisory phone number for Braille communication as well as an audiotape and large print. “We continuously try to learn more about how people are receiving our messages and better ways to do it. We are always trying to improve,” McCann said.

Besides fishing advisories posted online and in stores, Minnesota shares information with the state about fish consumption safety in alternative ways. “We work with health care providers. We have things on our website, YouTube videos. We have tasty videos about recipes,” McCann, the state Department of Health research scientist, said.

“We have done focus groups with woman to see how they want to receive information and what are the barriers in eating fish. We do surveys, and we work with communities that we think eat more fish, like the Hmong community in Minnesota,” she said.

Unlike the other Midwest states, the Missouri DNR engages a younger audience to understand fishing advisories early in their life. The state provides the public with a fish advisory activity book to engage young ones. This book contains information in an entertaining way about different topics like the biomagnification of mercury in fish, lead poisoning and the different types of fish.

Cedar Falls fisherman Troy Slater said he is conscious of the health effects of eating fish contaminated with chemicals. “I’ve talked to kids who have grown up in Cedar Falls who have fished the Cedar but won’t eat anything out of it just because of all of the runoff. I think about it,” he said.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login