At Risk: Nine out of ten school buildings are within pesticide drift zone

By Elise Leasure, Sabine Martin, Rachel Schmid, Tehya Tournier, Ben Boezinger, Saba Aydiner, Chase Kline, Sophia Schillinger

Photos by Ben Boezinger of Aldrich Elementary in Cedar Falls. With the expanding population of Cedar Falls, new schools are needed to accommodate the large amount of new students (Feature). Many Iowa schools are surrounded by corn and soybean fields which are sprayed in the early spring including Hudson High school (above).

Nine of every 10 public school districts in Iowa are within 2,000 feet of a farm field, making students and teachers susceptible to being exposed to pesticides that drift from the fields when pesticides are sprayed.

Yet many school officials interviewed for an IowaWatch/Tiger Hi-Line investigation showed little to no awareness on how pesticide drift could affect the staff and students in school buildings.

“You know, I hadn’t even thought of that,” Kim Cross said of the risk of spray drift. Cross is wrapping up as Cedar Falls Community School District Southdale Elementary principal before becoming principal at the new Aldrich Elementary in Cedar Falls that is to open the fall of 2018. “That was just something that I had heard recently that was a concern of someone,” she said.

The distance of 2,000 feet is based on a 2006 study by researchers led by M. H. Ward of the National Institutes of Health, who found an increased risk of potentially harmful pesticide spray drift from croplands at that proximity. To put 2,000 feet into perspective, the distance is about three city blocks in Iowa.

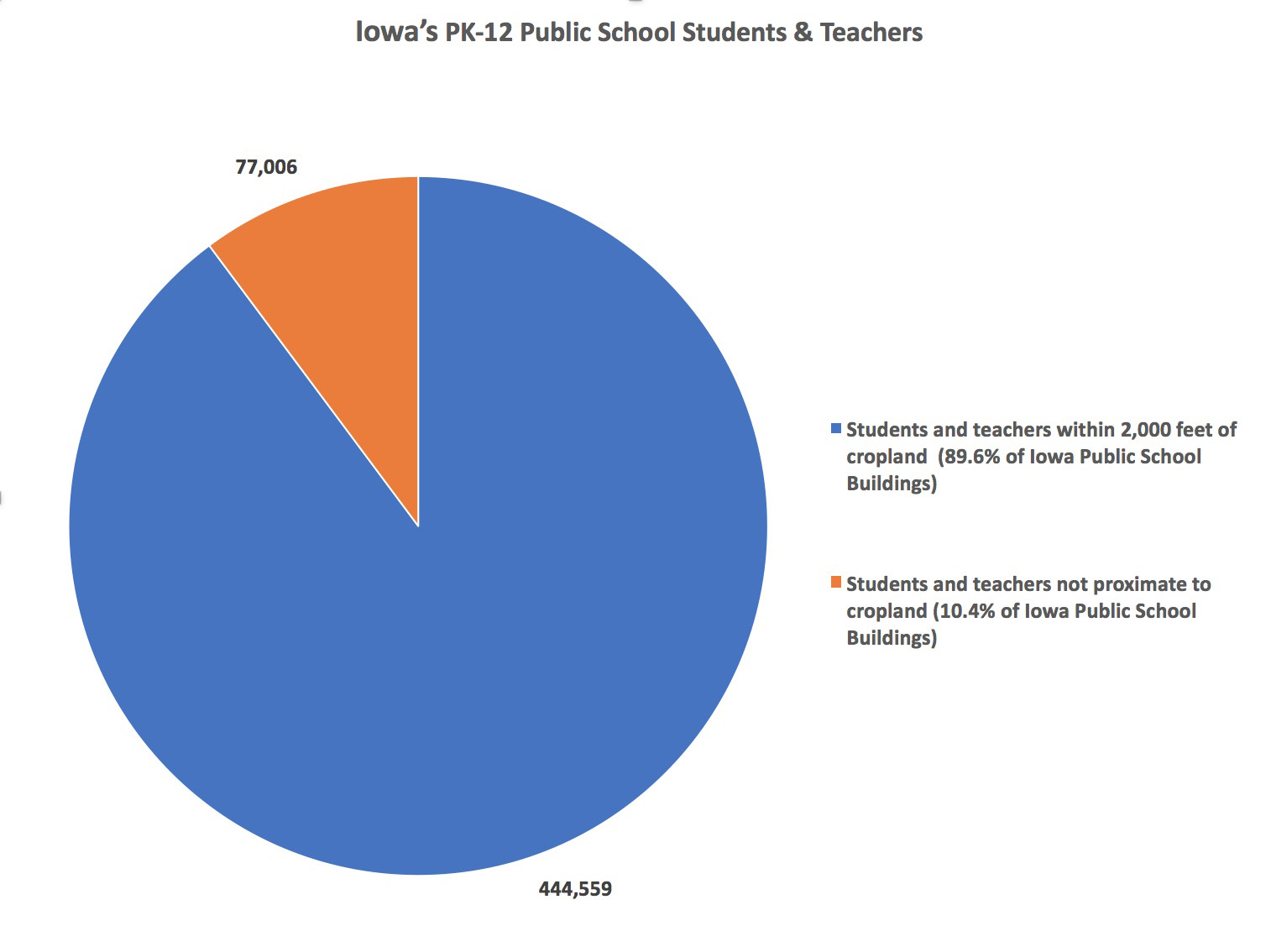

A journalism project published by Science in the Media, a University of Northern Iowa project, showed that 89.6 percent, or 1,183 of Iowa’s 1,321 K-12 public schools, are within the range of accidental spraying and spray drift. IowaWatch, a nonprofit news organization, and the Tiger Hi-Line, are media partners with Science in the Media.

With close to 1,200 schools being adjacent to the fields and in range of sprayings, 444,559 students and teachers are at risk to exposure and health concerns associated with pesticide exposure.

Louis Beck, an agriculture teacher at Union High School in La Porte City, Iowa, one of the schools among the 33.5 percent in Iowa directly adjacent to farmland, said the lack of buffer zones for pesticide application on farm fields worries parents and faculty he knows.

“As a teacher, I don’t know if there is anything sent out or part of any orientation to students or their parents, or anything like that,” Beck said. “I’d have to say that I really don’t know. I have not been made aware of any protocol that we are supposed to have.”

A pesticide is any chemical applied to crops to eliminate animals or insects that may harm crops. Spray drift can occur in two different ways: during application or by volatilization.

When a pesticide is applied, the chemicals can be carried by the wind to points away from the intended application site—a process known simply as “spray drift.”

The drift can then come in contact with other crops, animals, plants and even humans, in the form of “spray, vapor, odor or dust,” Iowa’s Center for Agricultural Safety and Health states.

Volatilization occurs when pesticides evaporate and rise into the air in a gas form. Even if pesticides can’t be seen physically, they can still be harmful.

“It happens a lot. Growers work really hard to keep that from happening,” Terry Basol, Iowa State Extension field agronomist, said of spray drift accidents. “Most growers and everybody who are spraying pesticides are very aware and take all the precautions that they can from things like that happening as much as they can.”

Early symptoms of acute pesticide poisoning after a single dose of pesticide include “headache, fatigue, weakness, dizziness, restlessness, nervousness, perspiration, nausea, diarrhea, loss of appetite, loss of weight, thirst, moodiness, soreness in joints, skin irritation, eye irritation, irritation of the nose and throat,” according to the Pesticide Safety Education Program of Cornell University.

The Cedar Falls Community School District is constructing the new elementary school within 2,000 feet of a farm field. “Even if that is exposed, it’s not right next to a crop field,” said Douglas Nefzger, the district’s director of business affairs and school board secretary.

Land where the school is being built was purchased jointly in 2007 by the city of Cedar Falls and the Cedar Falls School District. Nefzger said projected rapid population growth drove city planners to select the site, west of Hudson Road on Erik Road.

“I can tell you, if you look at the district maps, none of our current buildings are anywhere close to [agricultural] land,” Nefzger said. “The exception to that will be next year when Aldrich Elementary opens up.”

In November 2007, school children in Strathmore, California, were exposed to a pesticide spraying from a nearby field, causing many to become sick and dizzy. Another pesticide spraying at a sod farm in Kahuku, Hawaii, in 2007 resulted in the hospitalization of seven students from a nearby school.

The toxicity of a pesticide depends largely on the type of pesticide and the amount that is exposed, meaning symptoms can vary from case to case. According to the Pesticide Safety Education Program, while the general symptoms of acute pesticide poisoning can appear in people exposed to large quantities of pesticides, they can occur similarly in those exposed to “small, non-lethal” amounts of pesticides over time. Chronic pesticide poisoning is often indicated by the addition of symptoms such as “nervousness, slowed reflexes, irritability or a general decline in health.”

Health risks increase when students, who are in their developing years, are exposed. Often called the “silent pandemic,” a study by researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health and the Icahn School of Medicine stated that the harm of chemicals on children’s developing bodies results in serious neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD.

In a world where the use of chemicals has become increasingly popular in the last few decades, the impact of these chemicals has begun to show. The National Academy of Sciences estimates that one-third of neurobehavioral disorders are caused directly by pesticides. In the United States, 15 percent of all children have one or more developmental disabilities. This shows a 17 percent increase when compared to the previous decade.

Despite rising percentages of ADHD and autism in children, the chemicals used when spraying pesticides also cause cases of neurodevelopmental disorder in approximately 400,000 to 600,000 of the four million U.S. children born each year, according to the Pesticide Action Network. Although pesticides are not the only cause of developmental disorders, according to Pesticide Action Network, public health experts agree that the chemicals used in pesticides can trigger disorder side effects if the child has been exposed to pesticides over a certain period of time.

Based on a published study titled “Proximity to Crops and Residential Exposure to Agriculture Herbicides in Iowa,” in the Environmental Health Perspectives, houses that are closer to pesticide-treated farms were found to have more pesticide-related chemicals than other houses in their communities. “We collected dust samples and compared them to see the amount of pesticide exposures and we saw higher amounts of exposure in houses closer to farm fields,” John R. Nuckols, emeritus professor of environmental and radiological science at Colorado State University, said.

Only 18 percent of U.S. states require buffer zones between schools and farms, and Iowa isn’t one of them. Buffer zones act as a barrier between public buildings and farm fields. The invisible barrier can prevent spray drift onto nearby public school and other buildings, possibly eliminating or reducing the potential of harm that pesticides and herbicides cause.

The state’s Pesticide Bureau makes an investigation enforcement penalties are relatively minor. IDALS can not require applicators to pay for loss due to pesticide drift.

One main concern that Iowa Sen. David Johnson (I-Ocheyedan) has is that Iowa’s industry in agriculture has power to prevent change to regulations about pesticide use. “Industrial agriculture has its grip on this legislature. I’ve seen that before, and that generally stifles regulatory consideration when you have a legislature like it is now,” Johnson said.

State Rep. Norlin Mommsen (R-DeWitt), who rents a family farm in Clinton Iowa, called Mommsen Farms, said pesticide labels provide sufficient regulation for applicators. “If you look at a label of any herbicide, it already talks about wind speed, if you need a set back or a buffer area and all those things are already there. That has nothing to do with legislation, that has to do with the manufacturer and the government,” he said.

Rob Faux, an organic farmer near Tripoli, Iowa, since 2004, has been directly hit by pesticide spray drift. “The label said these are dangerous things. Then they should probably be calling when they are going to apply a dangerous thing on the field next to you, and you should probably be aware of it if it drifts or you need to take precautions. There is no such rule right now,” Faux said.

In Iowa, the labels on containers for these pesticides prescribe the only precautions farmers have to take, which in turn poses a threat to all students and faculty in buildings 2,000 feet away from farmland.

Pam Ziegler, director of elementary education for the Cedar Falls School District, said that urban growth along the west side of Cedar Falls has and will increase at such a rapid rate that she has no concern of potential spray drift toward the new elementary school and its effects. On the west side of Aldrich Elementary, for example, city-owned land eventually will be developed into a park area for the school, she said.

Of Cedar Falls’ nine open school buildings, all but two, Peet Junior High and Cedar Heights Elementary, are within a distance that could result in exposure to drifting pesticides, according to the 2017-2018 Iowa Public School Building Directory that the Science In the Media project used for its mapping analysis.

Cedar Falls’ school district does not have a formal plan if exposure to spray drift happened at a school, something which has not occured at a Cedar Falls school. “I think about the only thing the district could do is to bring that concern up to the landowner,” Nefzger said. “I know that the gentlemen that owns that property also owns other properties adjacent to residential developments in the community, so I can’t imagine that he would not be sensitive to our requests,” he said.

Bob Uhl, owner of the land adjacent to Aldrich Elementary, declined to comment on the story.

Cedar Falls Schools’ Nefzger said, “I think any time you see somebody out there on a 20 mph windy day spraying, that would raise a flag or two. I would like to think that most of our ag friends know that that is a waste of resources for them because the product is not being applied where they want it to be applied.”

More than 680 million pounds of pesticides are applied to U.S. agricultural fields each year, according to a report by the Pesticide Action Network. The Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship Health (IDALS) notes that there were 566 reports made to the IDALS Pesticide Bureau from 2012 to Aug. 1, 2017, and that drift incidents tend to be underreported.

In the last year complaints involving alleged pesticide drift have increased. IDALS received 215 misuse complaints in crop year 2017, compared to 91 in crop year 2016. Out of the 215 complaints in 2017, 179 were agriculture related.

The Iowa Pesticide Bureau has records regarding cases of spray drift and school from crop year 2006 to crop year 2017. Over this period, only one complaint has been recorded that includes allegations of pesticide drift from a neighboring property on school grounds. The outcome of the investigation determined that no pesticide application took place because the complaint mistakenly thought that the anhydrous ammonia was a pesticide. Because of the outcome, the complaint was dismissed.

The IDALS also received complaints from the general public regarding pesticide misuse by school personnel or or by individuals hired by the schools to perform pesticide application in the crop years of 2016 and 2017. Six complaints were documented of alleged children exposure pesticides due to misapplications on school grounds by school employees and four by by companies contracted by school to apply pesticides on school grounds. Nine complaints were recorded alleging that school personnel uncertified to spray pesticides performed job duties that they are not qualified for, and seven from school contracted non certified commercial applicators.

In Iowa, regulations for applying specific pesticides and herbicides go only as far as the label.

“It is really pertinent for anyone who is using products to pay attention to the label so they know the precautions to abide by,” Terry Basol, Iowa State Extension field agronomist, said.

In cases of reported spray drift, Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship’s Pesticide Bureau makes an investigation enforcement penalties are relatively minor. IDALS can not require applicators to pay for loss due to pesticide drift.

One main concern that Iowa Sen. David Johnson (I-Ocheyedan) has is that Iowa’s industry in agriculture has power to prevent change to regulations about pesticide use. “Industrial agriculture has its grip on this legislature. I’ve seen that before, and that generally stifles regulatory consideration when you have a legislature like it is now,” Johnson said.

State Rep. Norlin Mommsen (R-DeWitt) rents a family farm in Clinton Iowa, called Mommsen Farms. He says that pesticide labels provide sufficient regulation for applicators. “If you look at a label of any herbicide, it already talks about wind speed, if you need a set back or a buffer area and all those things are already there. That has nothing to do with legislation, that has to do with the manufacturer and the government,” he said.

Rob Faux, an organic farmer near Tripoli, Iowa, since 2004, has been directly hit by pesticide spray drift. “The label said these are dangerous things. Then they should probably be calling when they are going to apply a dangerous thing on the field next to you, and you should probably be aware of it if it drifts or you need to take precautions. There is no such rule right now,” Faux said.

A Scienceinthemedia.org chart shows the reletive distance of schools within 2000 feat of cropland. Only 10.4 % of students across Iowa are in a safe zone regarding spray drift, totaling to a whopping 444,559 students located in spray drift zones.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login