Increasing nitrate levels threatening drinking water from three of Cedar Falls’ eight public utility wells

By Staff Writers Elise Leasure, Sabine Martin and Katie Mauss

Because nitrates are invisible and tasteless, this illustration is a way to visualize it. By adding food coloring powder to one-liter containers of water to represent nitrates in water, the containers of water range progressively from 0 to 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 milligrams of food coloring. One can see increasingly how much the dye affects the visual quality of the water.

Sabine Martin and Tana Gam-Ad Illustration

Across the street and a few doors down from Meghan and Sean O’Neal’s Neola Street home in Cedar Falls you can see a small, nondescript one-story brick building. “I have seen that building before,” Meghan O’Neal said. “I never knew what it was.”

The building is Cedar Falls Utilities’ pump station 3, one of eight water wells that supply the city’s water system that has little identification except for a small sign attached to it that says Cedar Falls Utilities, the building’s address, and a phone number.

O’Neal and her husband are new to the neighborhood, but long-time Neola Street resident Rosann Good wasn’t aware of its purpose either, nor was Chuck Parsons, who has lived directly across the street from the pump station for two decades.

Knowing where one’s water comes from is one thing. Knowing what is in the water is another.

Three of Cedar Falls’ wells – 3, 9 and 10 – consistently have recorded high nitrate levels. All three are in the northern part of Cedar Falls and covered by a shallow layer of bedrock, which allows more nitrates to infiltrate the groundwater.

Pump Station 3 by Neola Street in Cedar Falls is one of three wells that supply Cedar Falls residents that has seen nitrate levels rising so much that Cedar Falls Utilities have to shut it down at times. Sabine Martin Photo

They stand in contrast to Cedar Falls’ southern water wells, where thicker bedrock layers better confine and protect the groundwater lower nitrate levels, a journalism collaboration of the University of Northern Science in the Media, the Cedar Falls High School Tiger Hi-Line and IowaWatch showed.

“CFU presently is able to keep its water at legal nitrate levels by diluting the higher nitrate water from the northern city pump stations with the lower nitrate water from the southern pump stations in the pipes,” Jerald Lukensmeyer, gas and water operations manager at the utility company, said.

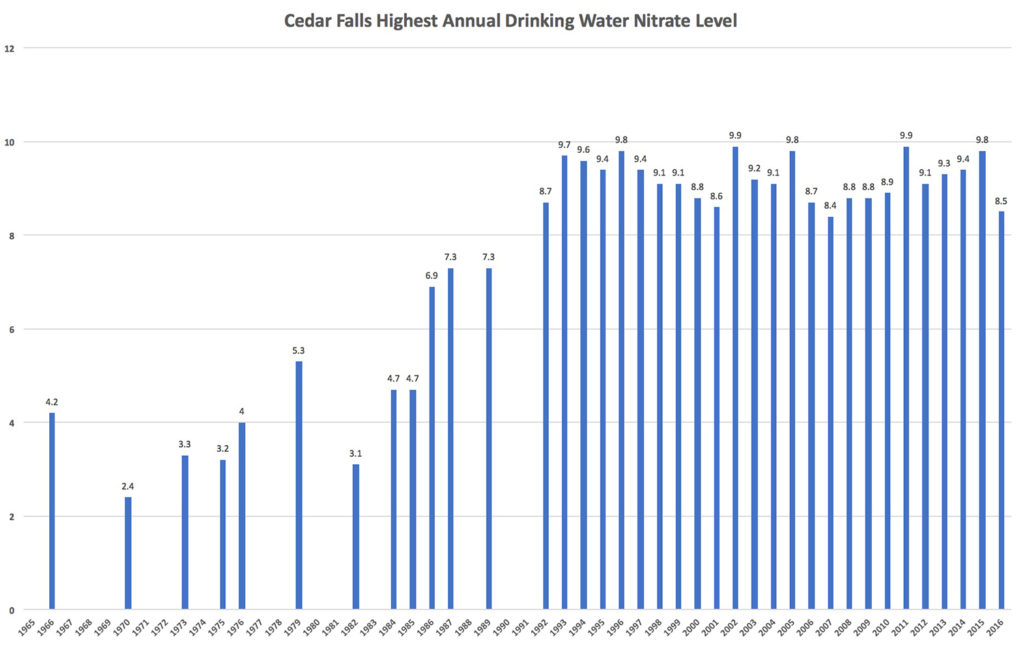

Reported levels in the city’s wells reached as high as 9.8 to 9.9 parts per million (ppm) in five different years from 1996 through 2016, Cedar Falls Utilities records show. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency lists 10 ppm as the limit of acceptable level.

Cedar Falls Utilities has records of nitrate testing levels dating to 1966, more than 50 years. In 1966, the highest nitrate reading at a city well was 4.2 ppm, far below the EPA’s 10 ppm limit. It wasn’t until 1992 that the highest nitrate reading exceeded 8 ppm. It has been between 8 ppm and 10 ppm ever since.

A 1999 U.S. Geological Survey study on Cedar Falls water supplies blamed the increasing application of nitrogen-based fertilizer to farm fields as the main cause of high nitrate levels. A 2013 Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship report, “Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy,” said 92 percent of nitrates in Iowa’s water come from runoff largely from agriculture land. The other 8 percent come from wastewater treatment plant discharges, the report said.

“As the runoff moves, it picks up and carries away natural and human-made pollutants, finally depositing them into lakes, rivers, wetlands, coastal waters and groundwaters,” the study explained.

“By definition, nitrate is a salt or ester of nitric acid, containing the anion no3-. Nitrate dissolves easily in water and is part of the nitrogen cycle,” said Peter Weyer, Interim Director of the Center for Health Effects of Environmental Contamination (CHEEC) at the University of Iowa.

Nitrates can appear naturally in drinking water at low levels. The EPA’s allowable drinking water nitrate level of 10 parts ppm is the same as 10 milligrams per liter.

NITRATES’ SIDE EFFECTS

A major side effect of high nitrates is blue baby syndrome, known in the medical world as methemoglobinemia and affecting infants who consume a high concentration of nitrates in a short period of time.

The body in instances like that converts the nitrates into nitrites. The nitrites then react with the oxyhemoglobin, or oxygen carrying proteins in the blood, to form methemoglobin, a protein that cannot carry oxygen. The body becomes deprived of vital oxygen if a large enough concentration of methemoglobin builds up in the blood, giving skin a blue hue. In severe cases, this can lead to digestive and respiratory system malfunction.

An average of more than nine of every 10 babies survive blue baby syndrome for at least 20 years after corrective surgery. Less than 1 percent of patients diagnosed with blue baby syndrome don’t survive after 30 days.

“Some birth defects have also been associated with a mother’s exposure to nitrate in drinking water. These include neural tube defects, limb deficiencies and cleft lip and palate,” Weyer said.

Other health concerns related to long-term nitrate exposure in drinking water studies conducted in Iowa have included bladder, ovarian and thyroid cancers, Weyer said.

Despite the side effects of high nitrate intake, many argue the acceptable U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s 10 ppm standard for a safe nitrate level should be raised, Weyer said. Because blue baby syndrome rarely is diagnosed, the argument could be that perhaps a 15 ppm or 20 ppm standard would be acceptable, he said.

“However, the cancer studies we have conducted show that the risk increases for long term consumption of drinking water that has nitrate concentrations at or above 5 ppm, or half the drinking water standard,” Weyer said. He added that other contaminants in water make it difficult to evaluate how contaminant mixtures in drinking water affect people.

The Cedar Falls water system’s eight wells are linked to an underground aquifer. These wells supply the water that all citizens drink. Cedar Falls Utilities tests drinking water nitrate levels quarterly. Wells consistently high in nitrates are tested more frequently.

Science in the Media: Since the early ’90s, nitrate levels have experienced increasing spikes in the well water provided by Cedar Falls Utilities.

Lukensmeyer, at Cedar Falls Utilities, said well 3 has been shut off at various times so that its nitrate level doesn’t exceed 10 ppm.

Despite the potential nitrates threat in Cedar Falls’ water supply, residents have faith in the water system. “I kind of trust Cedar Falls Utilities that they are doing a good job with that,” Neola Street resident Rosann Good said.

CHEMICALS FROM FARM RUN-OFF

Some states have passed laws with bipartisan support to curb farm chemical runoff. Minnesota requires buffers that aid the growth of perennial vegetation as far as 50 feet along rivers, streams and ditches, according to the Minnesota Department of Natural Resource’s website.

However, new water quality management has failed to gain serious footing in the Iowa Legislature, even following a recent federal lawsuit filed by Des Moines Water Works, an independent utility that provides clean water to 500,000 people in the Des Moines metro area.

The lawsuit said drainage from three Iowa counties in the Raccoon River drainage district contributed to high nitrate levels in runoff that the water company had to clean for drinking. A federal judge dismissed the lawsuit in March saying the state had to resolve the problem, not the drainage district.

“I was very disappointed with what occurred this year,” said state Sen. Bill Dotzler, a Democrat representing Waterloo, Evansdale, Elk Run Heights, Raymond, Washburn and Gilbertville. “We’ve been working backwards.”

Various pieces of legislation related to water quality have been introduced in the Legislature in response to the Des Moines Water Works lawsuit. One example, House File 316, aimed to eliminate the Des Moines Water Works board and give control of water quality to the local level through the creation of regional utilities rather than independent companies. The bill did not advance in the 2017 legislative session.

The Republican-controlled Legislature argued that House File 316 would give cities direct control over their water, but opponents of the bill and Des Moines Water Works supporters said they believed the bill was a power move to protect commercial agriculture and suppress water quality concerns due to finances.

“Farmers are trying to up their production, which you can’t blame them for, and they’ve basically been ignoring the Federal Water Protection Act for a long time,” Dotzler said. “Now they’re realizing people are getting more serious about water quality, and they’re afraid that any structures that they put in is all going to come out of their pocket.”

The question plaguing Iowans and their legislators is how to find a balance between protecting constituents and protecting Iowa’s bustling farm economy. According to the Iowa Farm Bureau, agriculture and its relative industries contribute $112.2 billion into Iowa’s economy and create one in every five jobs in the state.

Republicans overwhelmingly have jumped at the opportunity to protect the industry, while various groups such as County Conservation Commissions promote sustainable agriculture and pollution prevention. County Conservation Commissions have been working with farmers across Iowa to stimulate the installment of cover crops, establish buffer strips and implement no-till farming methods to improve the conservation of soil and the quality of water.

“We know that the amount of tiling has gone up across Iowa at an incredible rate, which draws the water down and accelerates the amount of nitrogen that is leached out of the soils into the watersheds,” said Dotzler, a 1966 Cedar Falls High School graduate who received a biology degree from the University of Northern Iowa before becoming a legislator. “You can’t blame a farmer. Tilling will give you about a 5 percent yield increase.”

Treating water for nitrate levels is costly but ignoring the contaminant, which comes at no immediate price, threatens the long-term quality of Iowa’s water, those arguing for water quality legislation said. “We need to address the water quality issue. Each year that we wait, we will just kick the can down the road, and the costs to fix the issue will continue to increase,” state Rep. Bob Kressig, a Cedar Falls Democrat, said. “Funding is very important, and we can create partnerships with cities, counties and farmers to make this possible. We have the expertise to work on the issue, but lack of funding is preventing them from being done.”

Little public awareness of water quality in the Cedar Valley may be preventing changes, too. Conversation about nitrates is minimal, as are public calls for reform or pressure on elected officials to make water quality a hot-button issue in the Iowa Legislature.

“Having clean water is very important to Iowa’s growth opportunities. We will have a difficult time attracting families to consider living in Iowa if our water is not viewed as not safe for drinking,” Kressig said. “We can do more to convince legislators that we need to make this a priority.”

The Des Moines Water Works federal court case and ruling should not affect how Future Farmers of America chapters in Iowa teach safe and healthy farming practices, Scott Johnson, Iowa FFA executive secretary, said.

“For the purpose of teaching the principles of science behind plant fertility, soil fertility and water quality, it shouldn’t change how this is taught as scientific principles behind the education should not be influenced by litigation,” Johnson said. “What does change is how current events such as the Des Moines Water Works lawsuit make this instruction more explicit — the instructor will/should connect students to current events as to help support why these principles are important to know and apply.”

Des Moines Water Works gives an example of where higher nitrate levels could lead. In 2015, it cost $1.5 million for “denitrification” of drinking water to remove nitrates and bring them down to a safe level for Iowa’s largest city, the utility reported. The utility is planning to spend $80 million on new denitrification technology in order to remove nitrates.

Dotzler said better education about water quality in Iowa is needed. He also said finding solutions should be a shared process. “People who live in cities need to work in a cooperative way to find alternatives for farmers,” Dotzler said.

“The Native Americans have a saying,” Dotzler said. “A frog does not drink up its own pond. What they’re trying to say is don’t use up your resources and farming practices with the high amount of runoff.’”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login